While the terrorist foot soldiers are fighting on the ground

in Syria, another battle is being fought behind the scenes, one to gain

influence over the global jihadi movement. This competition could raise the

terror threat against Europe and the United States to a new level, as both

groups aim to provide their capabilities.

ISIS started as a more

extreme offshoot of Al Qaeda (AQ) but its central command officially announced

on March 2014, that ISIS has no relationship with their leadership. Two groups

also began fighting around that time with conflicts taking place both on the

ground and ideologically.

In their fight for legitimacy over the jihadi movement, the groups will continue to fight each other, fight for control over Iraq, Syria and experts warn that these rival extremists could soon turn their attention to launching attacks on the West, in attempts to display their capabilities.

Two leaders behind this fight are ISIS chief and declared caliph Baghdadi and AQ chief and Islamic figure Zawahiri. In regards with the groups' leadership mind set; ISIS is putting more energy on an aggressive show, while AQ is structuring an influence network.

It won't be wrong to argue that AQ is extremely active in rural areas and among the poor, within the conflict regions. The group was able to reach out the minds of economically suffering territories through out the Middle East and South Asia creating deeply religious elements.

Al Qaeda's Syrian Offshoot Nusrah Front,fighting ISIS elements around western Syria's Yarmouk region.[AP, April 2016]

ISIS perception is much different however. They are being seen as a flash in the pan. People see its leader as a remnant of Saddam's Republican Guard, and when compared to Zawahiri, they see Baghdadi as having no Islamic Intellectual standing and no moral authority.

This view is part of the reason why ISIS is having trouble spreading beyond the conflict zones in Iraq and Syria. Outside of that, it has only managed to find some influence in destabilized environments in Libya and Afghanistan where it was able to lure some former members of the Taliban with "money".

Elsewhere, the situation is much different. Whether its the jihadi networks in Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Egypt, Qatar, Kuwait, UAE or Sudan, ISIS has had little luck shaking the foundations laid by Al Qaeda.

ISIS was able to make gains quickly but the noise it made drew to much attention and it is loosing momentum for a few months. For example, while Russians recently revealed that last year ISIS made up to 200 million USD from stolen antiquities from Palmyra alone, their financial channels in oil and looted antiquities have been hit hard by US, Russian and European efforts.

Al Qaeda on the other hand, brings in less cash but its black market income is a stable, steady some 25 to 30 million USD annually. With Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) alone, the extremists had 35 million USD at their disposal which they had gained mainly through kidnappings of Europeans in North Africa.

Recruitment has followed a similar pattern. ISIS was drawing large number of fighters early on, through often brutal propaganda and the promise of well-paying work. This has slowed however through hits to its finances and efforts to stop its online propaganda.

With Al Qaeda on the other hand, its links and networks to move fighters have been around since the war between mujahideen and Soviet Union (1979-1989). However both ISIS and AQ are often able to recruit young men because both are viewed as being against the dictatorships that are unfortunately common throughout the Muslim societies and both are able to offer work to people (not just as fighters but also as side duties for the shadow activities) in countries where opportunities are hard to find.

Most analysts agree that even if ISIS were defeated and the war in Syria ended, it would likely only drive ISIS to form a base of operations elsewhere, most likely in North Africa, and give Al-Qaeda even more notoriety. Al-Qaeda may actually have the long game "figured" out in Syria. Bashar Assad will likely stay in power. And in that environment, with ISIS gone, Al-Nusrah Front will likely be regarded as the most influential group that opposes the regime.

Al-Qaeda also has a much different approach than ISIS. While ISIS uses harsh violence and brutality for social control and dominance, -something that has damaged its influence among many local population and disturbed the fabric of religious identity- the approach Al-Qaeda uses is more about working by, with and through local populations.

Still, the balance of power could easily change. What ISIS has done is, to make good on some of Bin Laden's longer range plans. Laden's strategic theory rested on what he had called "the stronger horse" that if you could defy the super power and still be standing up, and actually the Muslim world would rally to you as the stronger horse. This theory was part of Bin Laden's plans with the September 11 attacks. But Laden made a miscalculation, and thought the US would fire a few cruise missiles back at him and he'd still be standing to some possible Special Forces or CIA operations. But instead; the US invaded not just Afghanistan but also Iraq, launched a large scale war on terror and eventually killed him in his hide-out in northern Pakistan.

ISIS on the other hand, has managed to launch terrorist attacks against the West and to seize territory for its caliphate, while still managing to remain standing, being the current "stronger horse". The goals of the global jihadi movement are to establish an Islamic Caliphate in Iraq and the Levant, and to attack the "enemies of Islam" in Europe, US and elsewhere.

With this in mind, we can say that what ISIS has done is to accomplish some of the things at an earlier stage in that organization's development, than Al-Qaeda was able to do. While Al-Qaeda still has support from many of the jihadi elites, the actions of ISIS are winning in the ideological battle between the two. Despite the headlines about ISIS losing ground in Syria and Iraq, experts agree that the war is far from over. No matter how things unfold in Syria and Iraq, both ISIS and AQ could prove significant threats in the region and beyond. If Assad falls and free elections are held in Syria, Al-Nusrah Front will likely be elevated to the political and possibly ruling class of Syria. They will not be seen as bad boys in the broad society, instead will be patriots and freedom achievers.

Regardless of how things develop, the jihadists who have pledged to fight for AQ or ISIS will likely find other conflicts to join, especially those who came from Europe. They will not have a path back to their country and a lot of those jihadists will be going from one conflict to another to assume the holly cause.

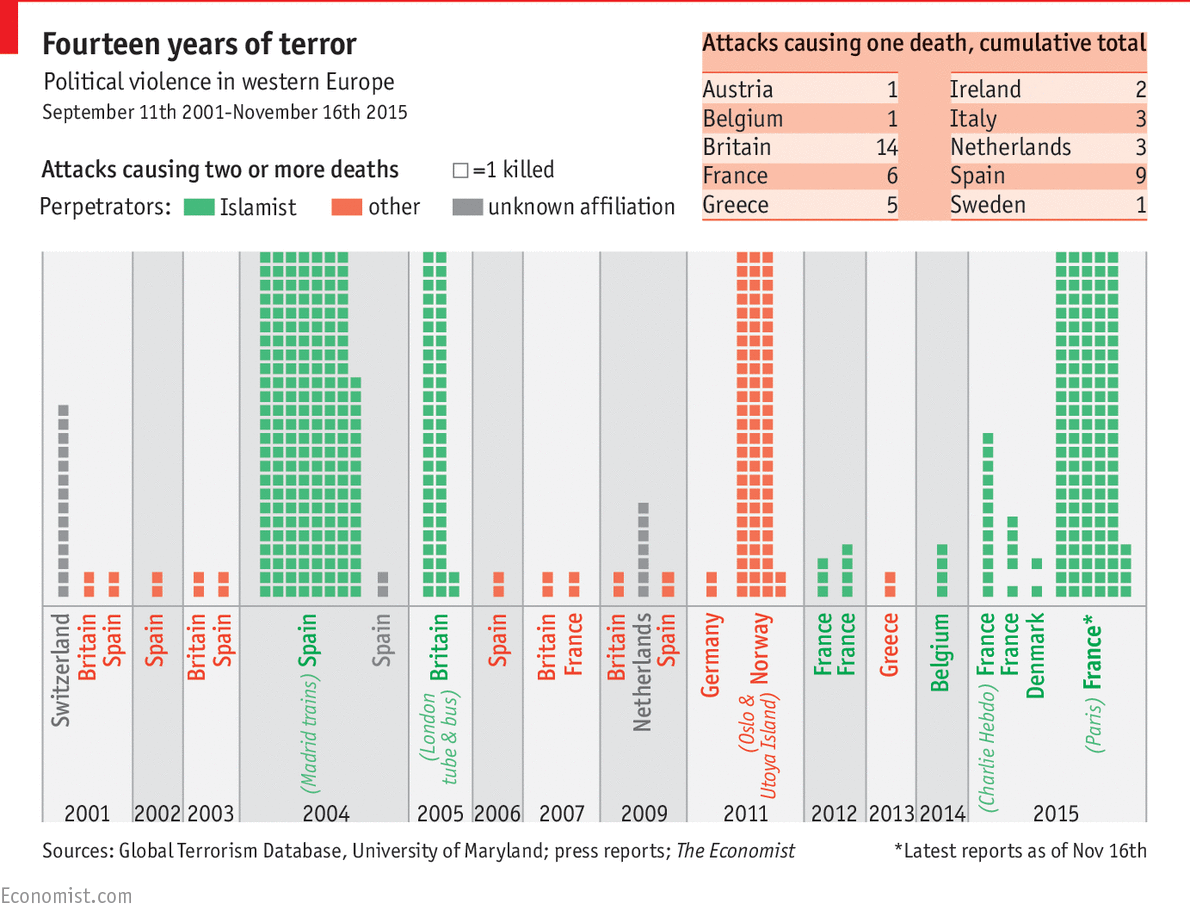

As the fighting dies down in Syria, or if either group is forced to flee, it's likely that some of them will take the road to Europe. This can lead to a situation similar to the Madrid Bombings, where one jihadi mastermind was able to convince moderate Muslims to launch a terrorist attack.

The war in Syria is not just a civil uprising. For ISIS and Al-Nusrah, the fight is rooted in the goals of jihadi movement, and the instability in Syria merely presented them with an opportunity to further these goals. Their goals are to influence the international system, starting with the Muslim world, then spreading out from there, as ISIS has started doing with its claimed caliphate.

The longer ISIS is allowed to hold its bases of power, the more credibility and respect the group will gain in the jihadi movement and the more danger it will present to the West. In the rural areas of many Muslims countries, AQ and ISIS have influence because they are viewed as being opposed to the dictatorships they live under.

By taking the sidelines, the US and Europe allowed jihadi groups to take the lead roles in the Arab spring revolutions, which only helped raise the notoriety of the radical Islamist movements. It is hard to sponsor any moderate group or national ally in the region, as there are many underhanded systems at play.

In Libya, jihadists who were part of the rebellion, now become stakeholders; Iran sponsors Hezbollah and Hamas, and uses Assad as a proxy; Turkey has passively supported jihadi movements by allowing fighters to join the Syrian war unabated.

There actually are two parts of radical Islamist movements. One part is the action arm. The terrorists and the fighters. The other part is the political arm, the ones who try to influence political systems and spread propaganda.

One of the best ways to combat ISIS-AQ like groups is to focus on combating their political arms, since this would degrade their notoriety. This will allow them to form bases of power and radicalize people to support their cause.

Al Qaeda functions as more of a somewhat loose network of jihadi groups that pledge their allegiance to it. The group started as a violent off shoot of the Muslim Brotherhood, which seeks to achieve the goals of jihad through open systems within societies. Much of AQ's direct political work is conducted through its political spoke-persons and influential imams.

With ISIS, much of its propaganda revolves around professionally made videos, its use of social media and its videoed horrible violence. As long as ISIS narrative goes unchallenged, they will continue to gain notoriety in the jihadi community and will likely be able to continue to hold their caliphate. Especially their attempts to retrieve chemical weapons should not be underestimated, since they have the desire, knowledge and required professional network to develop and pull off such an attack in any designated location.

In their fight for legitimacy over the jihadi movement, the groups will continue to fight each other, fight for control over Iraq, Syria and experts warn that these rival extremists could soon turn their attention to launching attacks on the West, in attempts to display their capabilities.

Two leaders behind this fight are ISIS chief and declared caliph Baghdadi and AQ chief and Islamic figure Zawahiri. In regards with the groups' leadership mind set; ISIS is putting more energy on an aggressive show, while AQ is structuring an influence network.

It won't be wrong to argue that AQ is extremely active in rural areas and among the poor, within the conflict regions. The group was able to reach out the minds of economically suffering territories through out the Middle East and South Asia creating deeply religious elements.

Al Qaeda's Syrian Offshoot Nusrah Front,fighting ISIS elements around western Syria's Yarmouk region.[AP, April 2016]

ISIS perception is much different however. They are being seen as a flash in the pan. People see its leader as a remnant of Saddam's Republican Guard, and when compared to Zawahiri, they see Baghdadi as having no Islamic Intellectual standing and no moral authority.

This view is part of the reason why ISIS is having trouble spreading beyond the conflict zones in Iraq and Syria. Outside of that, it has only managed to find some influence in destabilized environments in Libya and Afghanistan where it was able to lure some former members of the Taliban with "money".

Elsewhere, the situation is much different. Whether its the jihadi networks in Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Egypt, Qatar, Kuwait, UAE or Sudan, ISIS has had little luck shaking the foundations laid by Al Qaeda.

ISIS was able to make gains quickly but the noise it made drew to much attention and it is loosing momentum for a few months. For example, while Russians recently revealed that last year ISIS made up to 200 million USD from stolen antiquities from Palmyra alone, their financial channels in oil and looted antiquities have been hit hard by US, Russian and European efforts.

Al Qaeda on the other hand, brings in less cash but its black market income is a stable, steady some 25 to 30 million USD annually. With Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) alone, the extremists had 35 million USD at their disposal which they had gained mainly through kidnappings of Europeans in North Africa.

Recruitment has followed a similar pattern. ISIS was drawing large number of fighters early on, through often brutal propaganda and the promise of well-paying work. This has slowed however through hits to its finances and efforts to stop its online propaganda.

With Al Qaeda on the other hand, its links and networks to move fighters have been around since the war between mujahideen and Soviet Union (1979-1989). However both ISIS and AQ are often able to recruit young men because both are viewed as being against the dictatorships that are unfortunately common throughout the Muslim societies and both are able to offer work to people (not just as fighters but also as side duties for the shadow activities) in countries where opportunities are hard to find.

Most analysts agree that even if ISIS were defeated and the war in Syria ended, it would likely only drive ISIS to form a base of operations elsewhere, most likely in North Africa, and give Al-Qaeda even more notoriety. Al-Qaeda may actually have the long game "figured" out in Syria. Bashar Assad will likely stay in power. And in that environment, with ISIS gone, Al-Nusrah Front will likely be regarded as the most influential group that opposes the regime.

Al-Qaeda also has a much different approach than ISIS. While ISIS uses harsh violence and brutality for social control and dominance, -something that has damaged its influence among many local population and disturbed the fabric of religious identity- the approach Al-Qaeda uses is more about working by, with and through local populations.

Still, the balance of power could easily change. What ISIS has done is, to make good on some of Bin Laden's longer range plans. Laden's strategic theory rested on what he had called "the stronger horse" that if you could defy the super power and still be standing up, and actually the Muslim world would rally to you as the stronger horse. This theory was part of Bin Laden's plans with the September 11 attacks. But Laden made a miscalculation, and thought the US would fire a few cruise missiles back at him and he'd still be standing to some possible Special Forces or CIA operations. But instead; the US invaded not just Afghanistan but also Iraq, launched a large scale war on terror and eventually killed him in his hide-out in northern Pakistan.

ISIS on the other hand, has managed to launch terrorist attacks against the West and to seize territory for its caliphate, while still managing to remain standing, being the current "stronger horse". The goals of the global jihadi movement are to establish an Islamic Caliphate in Iraq and the Levant, and to attack the "enemies of Islam" in Europe, US and elsewhere.

With this in mind, we can say that what ISIS has done is to accomplish some of the things at an earlier stage in that organization's development, than Al-Qaeda was able to do. While Al-Qaeda still has support from many of the jihadi elites, the actions of ISIS are winning in the ideological battle between the two. Despite the headlines about ISIS losing ground in Syria and Iraq, experts agree that the war is far from over. No matter how things unfold in Syria and Iraq, both ISIS and AQ could prove significant threats in the region and beyond. If Assad falls and free elections are held in Syria, Al-Nusrah Front will likely be elevated to the political and possibly ruling class of Syria. They will not be seen as bad boys in the broad society, instead will be patriots and freedom achievers.

Regardless of how things develop, the jihadists who have pledged to fight for AQ or ISIS will likely find other conflicts to join, especially those who came from Europe. They will not have a path back to their country and a lot of those jihadists will be going from one conflict to another to assume the holly cause.

As the fighting dies down in Syria, or if either group is forced to flee, it's likely that some of them will take the road to Europe. This can lead to a situation similar to the Madrid Bombings, where one jihadi mastermind was able to convince moderate Muslims to launch a terrorist attack.

The war in Syria is not just a civil uprising. For ISIS and Al-Nusrah, the fight is rooted in the goals of jihadi movement, and the instability in Syria merely presented them with an opportunity to further these goals. Their goals are to influence the international system, starting with the Muslim world, then spreading out from there, as ISIS has started doing with its claimed caliphate.

The longer ISIS is allowed to hold its bases of power, the more credibility and respect the group will gain in the jihadi movement and the more danger it will present to the West. In the rural areas of many Muslims countries, AQ and ISIS have influence because they are viewed as being opposed to the dictatorships they live under.

By taking the sidelines, the US and Europe allowed jihadi groups to take the lead roles in the Arab spring revolutions, which only helped raise the notoriety of the radical Islamist movements. It is hard to sponsor any moderate group or national ally in the region, as there are many underhanded systems at play.

In Libya, jihadists who were part of the rebellion, now become stakeholders; Iran sponsors Hezbollah and Hamas, and uses Assad as a proxy; Turkey has passively supported jihadi movements by allowing fighters to join the Syrian war unabated.

There actually are two parts of radical Islamist movements. One part is the action arm. The terrorists and the fighters. The other part is the political arm, the ones who try to influence political systems and spread propaganda.

One of the best ways to combat ISIS-AQ like groups is to focus on combating their political arms, since this would degrade their notoriety. This will allow them to form bases of power and radicalize people to support their cause.

Al Qaeda functions as more of a somewhat loose network of jihadi groups that pledge their allegiance to it. The group started as a violent off shoot of the Muslim Brotherhood, which seeks to achieve the goals of jihad through open systems within societies. Much of AQ's direct political work is conducted through its political spoke-persons and influential imams.

With ISIS, much of its propaganda revolves around professionally made videos, its use of social media and its videoed horrible violence. As long as ISIS narrative goes unchallenged, they will continue to gain notoriety in the jihadi community and will likely be able to continue to hold their caliphate. Especially their attempts to retrieve chemical weapons should not be underestimated, since they have the desire, knowledge and required professional network to develop and pull off such an attack in any designated location.